Consumers love content. All kinds of content, from news, features and opinions to reviews, videos, infographics and listicles. It doesn’t seem to matter if it’s advertorial or editorial. They greedily consume it just the same. In fact, a recent study by researchers at Grady College in Georgia say most consumers have difficulty telling the difference between native advertising and editorial content.

This concerns the folks at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). So much so, that that FTC has issued guidelines for such ads. The goal, they say, is to keep consumers from mistaking online ads for news, reviews, videos and other journalistic or creative content. The guidelines apply to news and lifestyle publishing sites, content aggregators, social media platforms, messaging apps and other digital media.

“The FTC’s policy applies time-tested truth-in-advertising principles to modern media,” said Jessica Rich, Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection, in a press release. “People browsing the Web, using social media, or watching videos have a right to know if they’re seeing editorial content or an ad.”

Agreed. Still, that shouldn’t stop marketers from producing content that is so smart, so enriching, consumers won’t care if it’s native advertising.

At Brogan, we’re big fans of native advertising. When done well, native advertising is the content that helps solve consumers’ problems. It’s the Internet search engine response to what’s on people’s minds. “Bad credit?” Three ways to repair your credit score now. “Where should I deliver my baby?” Eight things to consider before you choose a hospital for delivery. “What’s collision insurance?” ABCs of collision insurance. “How do you roast beets?” Roasting beets with foil or oil.

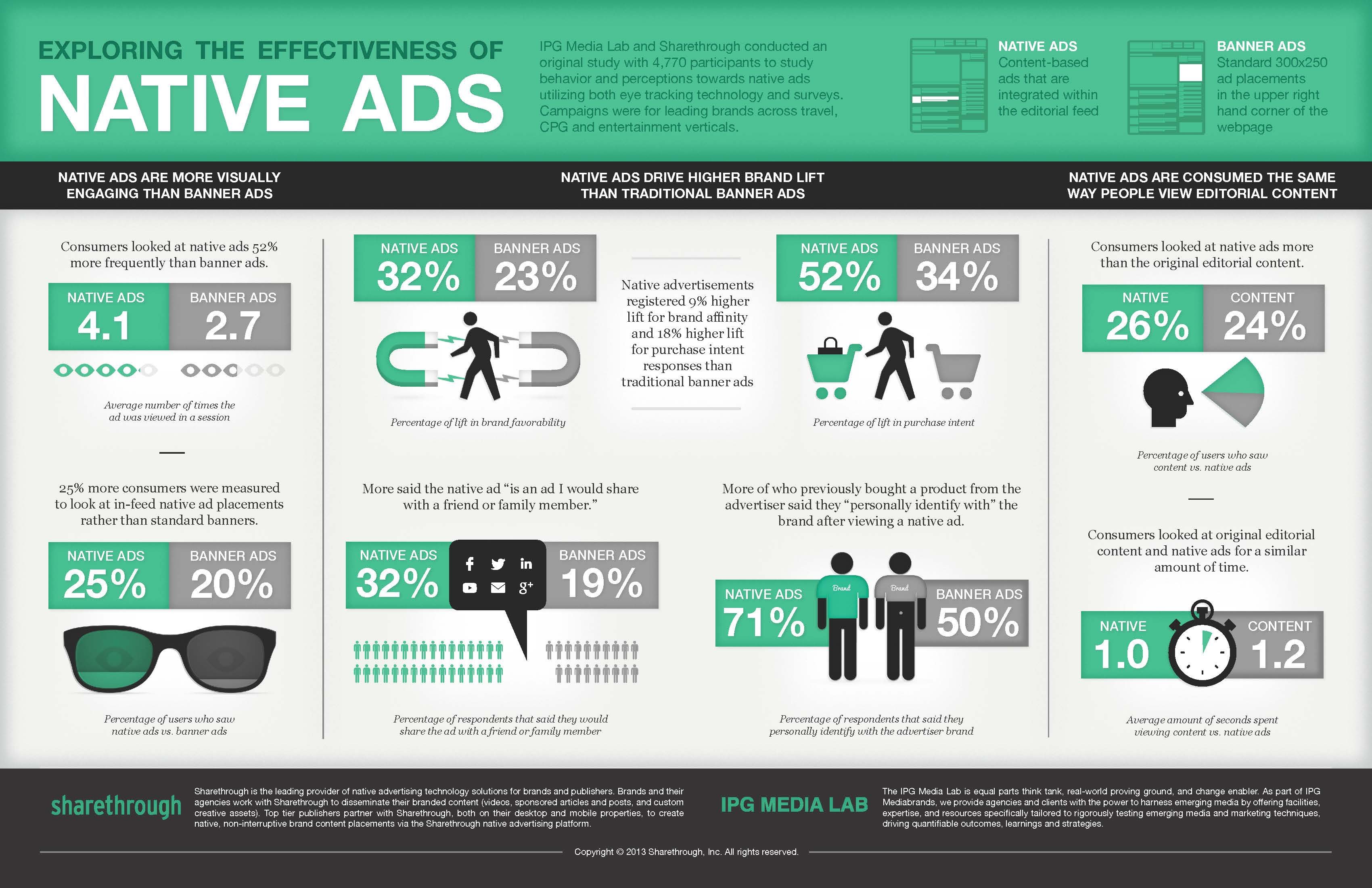

The proof is in the native ad performance.

And, right now, native advertising is getting more attention than many other forms of digital media. Native gets more than simple ad impressions, it motivates purchases by winning consumer interest and consideration. Consumers are not only reading the advertorial, they’re responding to calls-to-action, asking for more information and visiting brand sites to poke around for more.

If the ad content ultimately helps the consumer move forward, bingo! Job well done. Consumer is happy. Advertiser is happy. And the FTC is happy, in so long as it’s patently clear that your native ad isn’t confused with a real piece of balanced, objective journalism.

There’s the rub. Imagine you’re chewing on a Los Angeles Times story online about eviction rates, when you’re enticed by a colorful thumbnail image about “10 heathy fruits you should be eating.” If you look closely, you’ll spot language around the ad that says “sponsored links,” “paid content,” “from around the web,” or some such lingo. Sometimes you have to look really closely because the font size is often credit card offer disclosure small.

Of course you’re curious about the best fruits for your health, so you bite. Soon you’re learning all about the benefits of apples, figs and kiwi. So right about now, the FTC starts getting fidgety. As the guardians of consumer advertising, they want it patently clear that this part of your online content experience is, in fact, advertising and not another well-researched, expertly vetted article published by the Los Angeles Times.

The FTC guidelines specify that advertisers must clearly and prominently disclose that ads and marketing messages are just that. The disclosures should stand out, so they’re easy to notice, and should be easy for consumers to understand. The method of making the disclosure must fit the medium; for example, a multimedia ad might require an audio disclosure. Advertisers are also warned not to call an ad a “promoted story,” because it could be misleading.

The key word is “transparency.” According to the FTC guidelines, “An advertisement or promotional message shouldn’t suggest or imply to consumers that it’s anything other than an ad.”

So what does the FTC’s ruling mean for brand marketers?

While publishers are responsible for properly flagging native advertising, brand marketers should be equally transparent when developing content. You won’t win any points with consumers for tricking them into reading your ad content or pulling a bait and switch. The reason native advertising is flourishing is because consumers feel they get something out of it. Don’t pretend your content isn’t branded, and make sure it’s worthwhile.

The BuzzFeed native ad format works well for many brands, like the PeaceCorps. The service organization challenged readers to take a personality quiz to learn which country might best suit them. The content is engaging and highly shareable, and clearly branded. (Editor’s note: Brogan works with Peace Corps.)

Purina uses video for its native ad content series, “Dear Kitten.” It features an elegant, adult tabby tutoring a spry, orange kitten on the life of a domesticated housecat. On the family’s new dog: “Dear Kitten, you’ve probably noticed there’s a new thing in the house. It is called a dog. And I know this, because before you, I had a best friend named Peanut. Rest in Peace. At first I assumed Peanut was just a very ugly cat.” Purina is careful to bookend the spots with logos, product and CTAs.

These are great examples of how native advertising can extend the brand story beyond traditional advertising. It’s a soft-sell approach, inviting consumers to take a seat, and get comfortable without fear a salesperson will jump out from behind the reclining chair with a credit app. And they get the job done while being fully transparent. The FTC would most surely approve.

“Native” advertising is

“Native” advertising is synonymous with deceptive marketing. It’s pure sock puppetry. Nobody intentionally submits themselves to an advertisement and most people do feel angry when they realize that they’ve been deceived. Native advertising weakens journalistic integrity and drastically increases the potential for brand backlash. For example, because you’ve taken such a cavalier attitude toward this issue by using “native” advertising to advertise “native” advertising, I’ve decided to boycott one of your clients: Belly Bandit. An easy way to think about the pitfalls of “native” advertising is to move the the venue from the internet to a physical location. If you tried to do “native” advertising door to door or in a store, you would be arrested and jailed. What is the major difference between paying a journalist to write a fake news story promoting your product and paying a doctor a kickback to promote your drug to patients as if it were his own professional advice? (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_largest_pharmaceutical_settlements to get an idea of what happens when pharmaceutical companies do “native” advertising utilizing doctors). In addition, The premise that stamping the ad as “sponsored content”, or some other euphemism arrived at by intense grammatical gymnastics, somehow alleviates the ethical violations inherent in “native” advertising is just plain wrong. In fact, changing the name is evidence that marketers are aware that this practice would be easily condemned if it were directly called an advertisement. If people were made aware that the “content” was actually an advertisement and who was the provider of that advertisement BEFORE ANY of it was presented to the viewer at all, then I highly doubt that “native” advertisements would have anywhere near the amount of success they do now. They would have the same success rate as banner ads because, without the deception, “native” ads just don’t work – regardless of how many other “native” ads there are out there, like your post here, claiming that they do.

I couldn’t disagree more with

I couldn’t disagree more with the comment above mine. As far as I’m concerned, there are a few options, and by far the least annoying is native advertising. Would you rather see a GIANT FLASHING BANNER or an unobtrusive link? Would you rather read XYZ company is great, they’re awesome, here’s why they’re so amazing…or here’s a problem, and here’s a company trying to solve it (like most native ads). The thing you always have to remember about native ads is that you often click because there’s something you’re interested in (for example, fruits). But then, you can go off and research for yourself about fruits, after reading the initial argument in that ad!

Great explanation of Native

Great explanation of Native ads with an awesome infographic. Love to read. Thanks for sharing.